[ad_1]

There’s a lot to worry about with China these days: its military build up, human rights abuses, intellectual espionage, squelching of Hong Kong, and threats to Taiwan. But tonight, we focus on China’s undoing of key free market policies of the last 40 years that created the only global economy to rival our own. In a series of crackdowns against capitalism, strict controls have been put on booming sectors, huge private companies, and wealthy individuals. Policies all springing from the mind of one man.

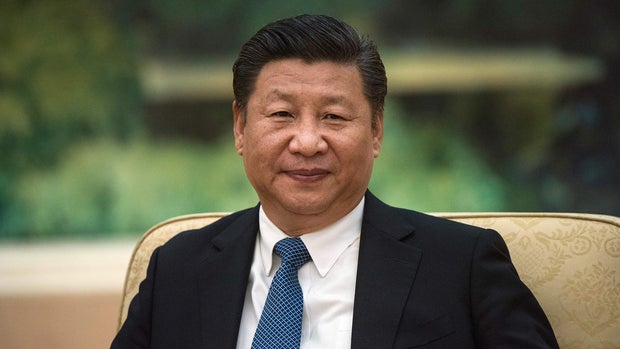

President Xi Jinping is positioning himself as big or bigger than Mao, and western analysts view his squeeze of the private sector as a powergrab.

Lesley Stahl: Are you surprised by the speed and the ferocity of these crackdowns?

Matt Pottinger: Yeah. It’s only the beginning is the, is the amazing thing.

Matt Pottinger was President Trump’s national security adviser on China and now writes about China at the Hoover Institution. To him, the recent crackdowns smack of Maoist repression.

Lesley Stahl: Xi’s defenders say that he’s not killing capitalism, he’s just modifying, getting rid of the excesses.

Matt Pottinger: I’ve always believed that the best interpreter of Xi Jinping is Xi Jinping himself.

Lesley Stahl: And what’s he saying in terms of capitalism?

Matt Pottinger: What he said in one of his most important speeches, he said: “We will see to it in this long struggle that capitalism dies out in the world” and that his vision of socialism prevails.

Keyu Jin: China grew really lawlessly, chaotically, in the last 40 years. And that’s all about to change.

Economist Keyu Jin splits her time between the U.K., where she teaches at the London School of Economics, and Beijing, where her father is president of one of China’s largest state-owned banks.

Lesley Stahl: Is Xi Jinping killing off capitalism in China?

Keyu Jin: President Xi envisions what he calls a “modern, socialist economy” for China, a much more restricted capitalism. President Xi is with the people. He is with the peasants, the middle class, and unlike his predecessors, he doesn’t really care so much about what happens to elites.

His attitude towards elites became clear about a year ago when he humbled Jack Ma, China’s most famous billionaire. Founder of Alibaba, the country’s biggest e-commerce company, Jack Ma had long tested Beijing’s patience with his global hobnobbing.

The boiling point came in October 2020, when Ma gave a speech criticizing the government’s rules and rule-makers as outdated and stifling innovation.

Keyu Jin: I was sitting in the third row.

Lesley Stahl: Did he take your breath away?

Keyu Jin: No, I wasn’t that surprised because he tends to be very vocal.

Lesley Stahl: He tended to be very vocal–

Keyu Jin: He tended to– thank you for the correction. He tended to be very vocal.

After the speech, Alibaba had to pay a hefty fine of nearly $3 billion for monopolistic behavior.

Worst yet: Ma was forced by the government to call off the $37 billion IPO of Ant, another one of his companies. And then, he seemed to vanish…

He resurfaced three months later in a video, quiet and subdued. But the message was loud and clear: China had had enough with its independent tech sector. Arguing it deepened the country’s wealth gap, authorities fined major social media and e-commerce companies for squashing competitors; delivery apps were chastised for underpaying couriers. One by one, their CEOs started stepping down and-or donating billions to government social projects.

Keyu Jin: They are just doing more philanthropy “voluntarily.”

Lesley Stahl: I like that you did that.

Keyu Jin: Yes, no, no, no, it’s true. “Voluntarily” doing more philanthropy. Treating their workers better.

Lesley Stahl: To the West, it looks like Xi is killing off the golden goose. Sabotaging what has made China the economic power that it is.

Keyu Jin: That is a complete misinterpretation of what is going on. China’s tackling the most intractable problems of Western capitalism ahead of the West. The concept of reducing income inequality has to be done all over the world, except that China’s just much faster at implementing some of these policies.

Lesley Stahl: But isn’t it communist?

Keyu Jin: No. Because it is really just to give more opportunities to the middle class, and not have the top 1% take away all the opportunities. These companies have a big control over, over the people.

Lesley Stahl: And now the government will have that.

Keyu Jin: The government wants to take that back. Absolutely.

Matt Pottinger: The purpose is to instill fear and to instill loyalty among those who are lucky enough not to get purged under, under the current campaign.

Matt Pottinger says the purge is not about creating a fairer society, but over who’ll know more about China’s citizens: the companies or the Communist Party. He points to a law that took effect last month giving officials deeper control over private personal information.

Matt Pottinger: The party has taken a machete and sort of whacked its way toward the headquarters and C-suites of all of these big tech firms and said, “Your data is now our data.”

Lesley Stahl: Do you think that the purpose, the purpose in a lot of these crackdowns is for the government to get their hands on the data?

Matt Pottinger: The Chinese government has said that data is like the new oil of this century and that– that where the data flows, power will flow.

Lesley Stahl: The new privacy law, it’s a big deal. What are the major concerns, especially for us in the West?

Matt Pottinger: If you are an American company operating in China, you are required to hand over your encryption keys to the Chinese government. What these new rules say is that they by law now also have control of your data.

One reason for this, the government says, is to keep China’s data from reaching foreign hands through the private sector. One company they targeted was DiDi,

China’s version of Uber. Its app and fleet collected data on its passengers and on China’s infrastructure.

DiDi’s problem started in June, when it had gone public with an IPO on the new york stock exchange, but–

Matt Pottinger: Only several days after that IPO occurred, Beijing suspended the app, basically made it impossible for people to download the app. And they sent the Ministry of State Security, which is China’s KGB, into the offices of DiDi to start assessing and taking control of DiDi’s data.

Fred Dufour / AFP/Getty Images

It’s not just data. The government is also clamping down on daily life and culture. This summer, authorities went after video gaming companies and enacted surprising restrictions.

Lesley Stahl: There’s a new law where kids can only play video games three hours a week.

Keyu Jin: Yes.

Lesley Stahl: And that was just by edict, period. And only on the weekends?

Keyu Jin: That’s correct. And I have heard many of my friends internationally saying they wish that they could have that too.

Lesley Stahl: Oh yeah! But it would never work in the United States. Parents don’t want the government to tell us what to do.

Keyu Jin: It is anathema to many, the kind of paternalism that is exerted on society. But really if you ask the Chinese people. The majority, they are very happy with how quickly it’s been done.

Nowhere was this more obvious than when they demolished the giant private after-school tutoring industry prepping kids for exams. Professor Jin says it was an example of free market capitalism run amok – draining the resources of parents. So one weekend in July – just like that – the government essentially outlawed this entire $120 billion for-profit sector.

Keyu Jin: If they’re determined to do one thing, they just do it. They don’t care about the capital markets, implication of the financial sector. They don’t care about the employment implications.

In other cases, the government is taming capitalistic excesses more slowly, like the bloated real estate sector. We visited China’s ghost cities 8 years ago, with their miles of empty skyscrapers with no residents, malls with no shoppers. Today, the government is gradually dismantling Evergrande – China’s second largest real estate company which overbuilt and took on more debt than any property developer on earth.

But all these actions against private industry are contributing to a slowdown in the Chinese economy and caused global investors to lose more than a trillion dollars this past summer.

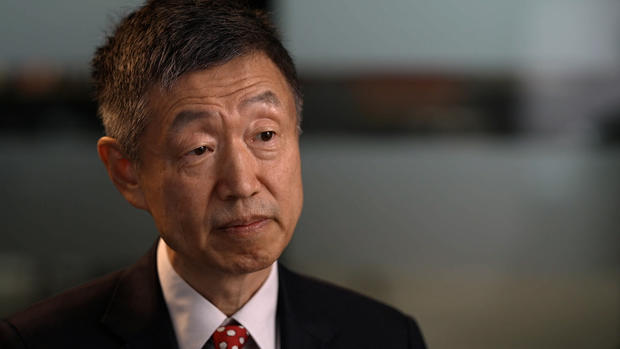

Weijian Shan: China has developed itself by embracing a market economy. In essence – capitalism. If they revert back to the centrally planned system, 40 years ago, it was already proven to be failed system.

Weijian Shan should know. He’s the CEO of PAG, a $45 billion private equity firm based in Hong Kong, where China has recently stifled democratic protest. Shan grew up during the decade of Mao’s cultural revolution that decimated the economy, killing and uprooting millions.

Weijian Shan: I was sent to the countryside. Mao wanted us to learn from the poor, from the peasants. So, I and many of my peers were sent to the Gobi Desert. We worked extremely hard. One time we worked nonstop for 31 hours.

But by his 20s, China under Deng Xiaoping had adopted the free market, and Shan went to study in the U.S. He even taught at Wharton, and today he’s investing for American pension funds and university endowments.

Lesley Stahl: I was about to ask why any American would invest right now in China, it’s so unpredictable.

Weijian Shan: Well, investment is a risky business. China, as a market, is not for faint-hearted.

Lesley Stahl: You don’t know what the leadership’s going to do tomorrow. We’re being told by economists that this is a move back to Mao Zedong’s state-controlled economy.

Weijian Shan: I think that’ll be too far to suggest but I must say that the way that they have done it very often is very clumsy.

Lesley Stahl: There’s no question that the tension between China and the United States is rising. We’re certainly competitors now in a heightened way. Shouldn’t that give people pause about pouring money in?

Weijian Shan: Well, think about it. China is the holder of Treasury bills to a tune of 1 trillion U.S. dollars. There’s more Chinese money in the United States than American money in China. So, if you’re worried about the competition between the two countries, who should be more worried?

He argues that China’s economy is still a good bet because their market is so big with 1.4 billion consumers. And there’s some merit, he says, in Xi’s state intervention, if compared to the United States.

Weijian Shan: I’m a free market…

[ad_2]

Read More: The rollback of free market policies in China