[ad_1]

The US economy will tip into a recession next year, according to nearly 70 per cent of leading academic economists polled by the Financial Times.

The latest survey, conducted in partnership with the Initiative on Global Markets at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, suggests mounting headwinds for the world’s largest economy after one of the most rapid rebounds in history, as the Federal Reserve ramps up efforts to contain the highest inflation in about 40 years.

The US central bank has already embarked on what will be one of the fastest tightening cycles in decades. Since March it has raised its benchmark policy rate by 0.75 percentage points from near-zero levels.

The Federal Open Market Committee gathers once again on Tuesday for a two-day policy meeting, at which officials are expected to implement the first back-to-back half-point rate rise since 1994 and signal the continuation of that pace until at least September.

Almost 40 per cent of the 49 respondents project the National Bureau of Economic Research — the arbiter of when recessions begin and end — will declare one in the first or second quarter of 2023. A third believe that call will be delayed until the second half of next year.

The NBER characterises a recession as a “significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months”. Just one economist pencilled in a recession in 2022, with a majority predicting monthly jobs growth to average between 200,000 and 300,000 for the remainder of the year. The unemployment rate is set to steady at 3.7 per cent, according to the median estimate for December.

The survey results, which were collected between June 6 and June 9, run counter to the Fed’s stance that it can damp demand without causing substantial economic pain. The central bank predicts that, as it raises interest rates, employers in the red-hot US labour market will opt to pare back historically high job openings as opposed to laying off staff, in turn cooling wage growth.

Jay Powell, the Fed chair, has conceded that the Fed’s efforts to moderate inflation may cause “some pain”, leading to a “softish” landing that sees the unemployment rate rise “a few ticks”. But many of the economists polled are concerned about a more adverse outcome given the severity of the inflation situation and the fact that monetary policy will need to shift towards much tighter settings in short order to address it.

“This is not landing a plane on a regular landing strip. This is landing a plane on a tightrope, and the winds are blowing,” said Tara Sinclair, an economist at George Washington University. “The idea that we are going to bring incomes down just enough and spending down just enough to bring prices back to the Fed’s 2 per cent target is unrealistic.”

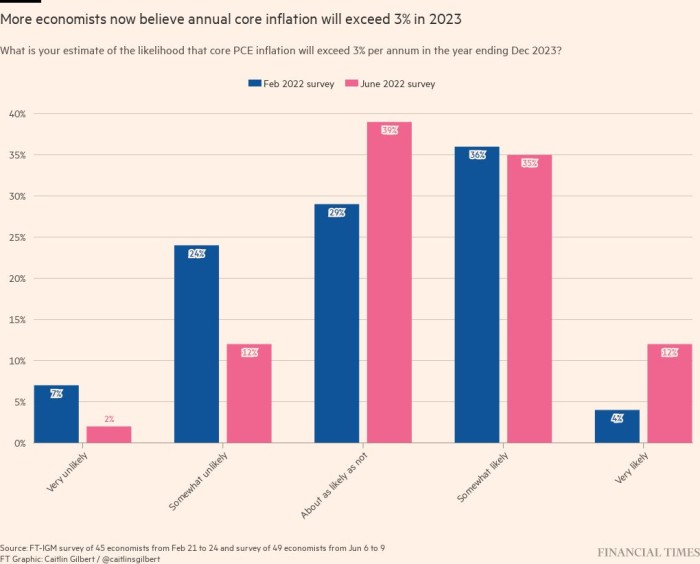

Compared to February’s survey, more economists are now of the view that core inflation, as measured by the personal consumption expenditures price index, will exceed 3 per cent by the end of 2023. Of the June respondents, 12 per cent thought that outcome was “very likely”, up from just 4 per cent earlier this year. The share of economists surveyed who thought that level “unlikely” over the same time period has since nearly halved.

Geopolitical tensions, and the increase in energy costs that is likely to accompany that, were cited overwhelmingly as the factor potentially keeping upward pressure on inflation over the next 12 months, followed by prolonged supply chain disruptions. By year-end, the median estimate for core inflation is 4.3 per cent.

Jonathan Wright, an economist at Johns Hopkins University who helped to design the survey, said the notable pessimism around both inflation and growth has stagflationary undertones, although he noted the circumstances are far different than the 1970s, when the term embodied a “much nastier mix of high inflation and recession”.

Nearly 40 per cent of the economists warned that the Fed would fail to control inflation if it only raised the federal funds rate to 2.8 per cent by the end of the year. This would demand half-point rate rises at each of the central bank’s next three meetings in June, July and September before downsizing to its more typical quarter-point cadence for the final two gatherings of 2022.

Few respondents expect the Fed to resort to 0.75 percentage point increases.

Further rate rises are also likely well into next year, says Christiane Baumeister, a professor at the University of Notre Dame who thinks the Fed could lift its benchmark policy rate as high as 4 per cent in 2023. That is just above the level the majority of economists surveyed believe will be the peak of this tightening cycle.

Dean Croushore, who served as an economist at the Fed’s Philadelphia branch for 14 years, cautioned that the central bank may need to eventually raise rates to roughly 5 per cent to contain a problem he believed was largely caused by the Fed waiting “far too long” to take action.

“It’s always tough to bring inflation down once you let it out of the bottle,” said Croushore, who now teaches at the University of Richmond. “If they would just accelerate the rate increases a little bit more, it might cause a little financial volatility in the short-run, but they might be better off by not having to do as much later.”

[ad_2]

Read More: US set for recession next year, economists predict