[ad_1]

As dawn broke on the first morning of 2021, dark storm clouds hung over Britain’s economic landscape. Hospitality, aviation and tourism had been at a standstill for much of the previous year, while high street retail had fared only a little better.

A winter Covid-19 surge heralded yet another punishing lockdown and, as if that wasn’t enough, Brexit was crimping Britain’s international trade. Consumer confidence languished at rock bottom with no end to the pandemic in sight.

Twelve months on, the world of business and finance has been on a rollercoaster ride, flitting from summer optimism to autumn supply chain chaos, before the Omicron variant of Covid-19 brought us back down to earth with a chastening bump.

In some respects, things are looking up. In others, it feels like we’re right back where we started. As Britain battles to recover from the pandemic body blow, here’s how the year unfolded.

Pings, petrol panic and supply chain pandemonium

The neologism of 2021 was surely “pingdemic”. Covid-19 restrictions were fully lifted on 19 July, unshackling large swathes of the economy in readiness for a summer rebound. But already workers who had been near to someone who later tested positive were being “pinged” with alerts from the NHS Covid-19 app, forcing tens of thousands to self-isolate. The trend caused massive disruption, affecting everyone from independent restaurants and shops to the likes of Asos, Rolls-Royce and Nissan.

The relaxation of self-isolation rules eased the problem somewhat, but it was far from the last setback to the UK’s recovery. Ping or no ping, labour supply issues persisted, due partly to the pandemic and partly to a dearth of overseas workers caused by Brexit.

Sectors from farming to hospitality struggled with staff shortages, but nowhere were the effects more visible than in the deficit of HGV drivers. New rules for EU hauliers, coupled with poor working conditions, red tape and a backlog at driving test centres, left the UK with a stark deficit of people qualified to get behind the wheel of delivery lorries. Supermarket shelves began to look sparse and stores including Tesco and Sainsbury’s even resorted to hiding the gaps with pictures of asparagus, carrots, oranges and grapes.

Perhaps the most striking consequence was the chaos at the petrol pumps. After BP warned in September that it didn’t have enough tanker drivers to deliver fuel to some forecourts, its concerns became a self-fulfilling prophecy as panic-buying caused many forecourts to run dry for days at a time. The crisis soon subsided but underlying supply chain problems remain an ever-present threat.

Gas prices, energy suppliers coal and Cop26

Alongside the fuel panic, the UK experienced a second autumn energy crisis, one made all the more poignant by the Cop26 climate conference in Glasgow. Wholesale gas and electricity prices began a prolonged surge from September on the back of a mix of factors including increased demand as countries unlocked, Russian restrictions on pipeline flows to Europe and low renewable power generation.

Energy suppliers collapsed like dominos as the market price for gas far outstripped what customers were paying under the government-imposed energy price cap. Between August and December, 25 went under: the largest was the “too good to be true” green supplier Bulb Energy, with 1.6 million customers, which became the first to enter the government’s “special administration” scheme for energy providers. The chain of failures has led to widespread calls for a rethink of the regulatory system that aimed to encourage competition by allowing smaller players to enter the market.

It wasn’t just suppliers that were hit. Sectors that use a lot of energy, such as steel, glass and chemicals, were brought to the brink of shutting down by the high cost of gas and electricity. Two fertiliser plants did stop operations, forcing the government to step in to help their owner, CF Fertiliser. Its two plants supply about 60% of the UK’s carbon dioxide, which is vital for the food and drink supply chain.

Luckily, the Cop26 summit was on hand to map out a path towards decreased reliance on fossil fuels. Opinion was divided on its success. Boris Johnson hailed a “big step forward”, but commitments from China and India on coal phase-out didn’t go far enough for many. Cop26’s biggest winner was surely AG Barr, the owner of Irn-Bru, which seemed to garner as many mentions as climate change.

Rows, trials and scandals

One of the year’s most acrimonious disputes came at the very start, as the European Union and AstraZeneca clashed over claims that the Anglo-Swedish pharmaceutical giant had reneged on its promise to deliver jabs. The row went to court before being settled in September after the firm agreed to deliver 200m doses by March 2022.

Also crying foul were politicians and campaigners who had hoped that the northern leg of HS2 would help boost economic growth in part of the country hampered by poor connectivity. In the end, the government’s scaled-back Integrated Rail Plan published in November ditched the proposed spur from Birmingham to Leeds, prompting accusations that the plan was not so much rail as betrayal.

The return of international travel in the summer was great news for tour operators and airlines but there was frustration among holidaymakers at the service offered by the host of firms that sprang up selling the required PCR testing kits. Many appeared to have been incorporated hurriedly to cash in on new market. After many tales of poor service and withheld refunds, the health secretary, Sajid Javid, vowed to crack down on “cowboy” firms.

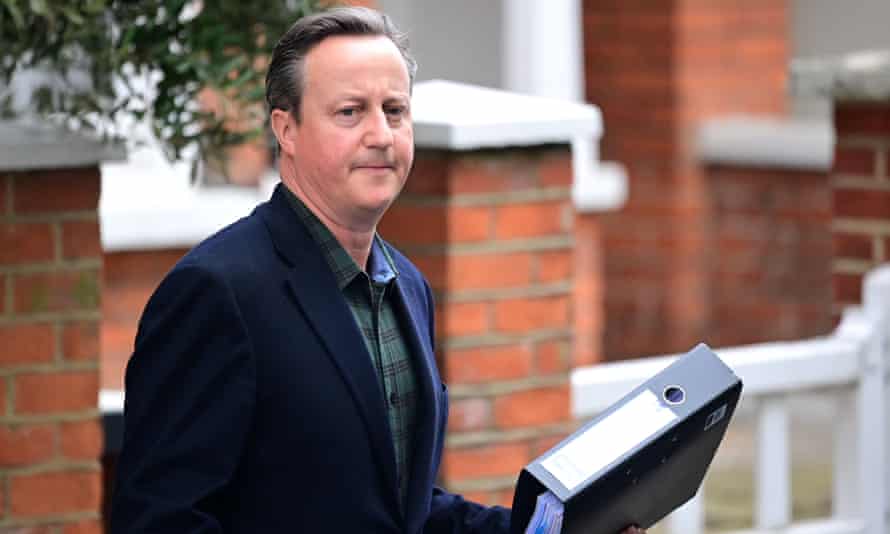

Two of the year’s biggest scandals starkly illustrated the gulf between the powerful and the voiceless. One was the Greensill affair, in which it emerged that the Australian financier Lex Greensill had been ushered into the heart of David Cameron’s government, where he appeared to have enjoyed carte blanche to insert his company into government procurement contracts, with lucrative results. After Cameron left office, he lobbied for Greensill Capital to receive government emergency support as it hurtled towards collapse. The affair’s fallout includes a Serious Fraud Office investigation into the links between Greensill and Sanjeev Gupta, the man who owns much of the UK steel industry.

Rather less powerful than Cameron and Greensill were the hundreds of postmasters wrongfully convicted of offences including theft on the basis of software errors in the Post Office’s IT system. Many had their names belatedly cleared in court this year, and the government has set aside up to £233m to compensate those forced to cover imaginary shortfalls. Many died before their names could be cleared, having had their reputations dragged through the mud by their employer’s aggressive pursuit on incorrect evidence.

As the year drew to a close, a jury was deliberating in the trial of Elizabeth Holmes, the founder of the US blood testing company Theranos. She denies 11 criminal charges alleging that she duped investors and patients by hailing her company’s technology as a medical breakthrough when results were actually error-strewn. The case has attracted worldwide attention, in part due to the incredible rise-and-fall narrative of Holmes, who started Theranos as a 19-year-old college dropout and became a paper billionaire before the company’s collapse.

Digital currency and meme stocks

At the very start of the year, the Tesla boss, Elon Musk, became the world’s richest man, overtaking Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, as shares in the electric vehicle-maker soared on the back of hopes that a Democrat-controlled US Senate would lead to better conditions for green technology. The increase pushed Musk’s net worth to £136bn.

Musk displayed an uncanny ability to move markets with a comment on Twitter. When the billionaire space-botherer said Tesla would resume accepting payment in bitcoin, the value of the currency moved past $40,000.

Even without Musk’s rocket fuel, bitcoin continued its rise, soaring above an all-time high of $68,000 in November. Even Dogecoin, a cryptocurrency invented as a joke, offered the promise of major returns, surging 14,000% between January and May. The Bank of England has since warned that bitcoin could end up worthless, but in truth its future is anybody’s guess.

The growing influence of social media on markets was further evidenced by the emergence of “meme stocks” – shares that attract investment purely thanks to online hype. The archetypal example was GameStop, a bricks-and-mortar video games outlet that offered little as an investment prospect until small traders latched on to it in January in a vigilante effort to squeeze hedge funds that had bet against it. The trend has caused wild fluctuations in GameStop and other meme stocks. One London-based hedge fund, White Square, was even driven under.

The phenomenon was fuelled by web forums such as Reddit and the growing trend for small investors to dabble in securities via trading apps such as Robinhood and eToro.

Deals, takeovers and market moves

As new technology flexed its muscles, the chancellor, Rishi Sunak, sought to make Britain more attractive for innovative companies to float in London by loosening listing rules. Deliveroo was a poster child for the policy but its float duly flopped.

More established UK names proved more attractive, attracting the attention of deep-pocketed private equity buyers. The supermarket chain Morrisons succumbed to a £6.9bn takeover by the US firm Clayton, Dubilier & Rice (CD&R). American buyout houses also took aim at the outsourcer G4S, the infrastructure builder John Laing and the defence companies Meggitt and Ultra Electronics.

Perhaps the most controversial takeover had nothing to do with private equity. The asthma inhaler maker Vectura was snapped up for £1.1bn by the cigarette company Philip Morris International. The tobacco firm claimed the deal was part of its switch to a “smoke-free future” but anti-smoking groups were up in arms and several medical conferences cut ties with Vectura after the deal.

For the FTSE100 it was a year of recovery. An initial slump was followed by gains that saw the blue-chip index finally return to its pre-pandemic crash level…

[ad_2]

Read More: The ups and downs of business, politics and economics in 2021